Shack Love

Watching the first shots of the digital revolution from a front-row seat in the suburbs.

SCENES FROM a 1970s suburban childhood, remembered fondly through shag-colored glasses:

Opening my big 10th-birthday present in April 1978: a red, molded plastic Realistic cassette recorder of my very own, which meant I could stop using my father’s university-grade recorder and tape my own songs off WXKX-FM, Pittsburgh’s pre-eminent Top 40 station at the time. (Cutting-edge method: Sit on floor of bedroom, push built-in mic right up to the radio’s speaker, hold breath and hope for a good recording.)

Eyeing the next-door neighbors’ 40-channel CB with envy and watching as their family’s older siblings summoned truckers passing along the nearby Pennsylvania Turnpike with a still-novel “Breaker, Breaker.”

Huddling under the covers late at night when the AM signals tended to travel farther, using my Archer multiband radio to pull in music from CKLW-AM in Windsor, Ontario, and, on the clearest evenings, a Cubs game on WGN-AM in Chicago.

Weekend afternoons at a table in the family room with my father, trying to create one of the sundry gadgets that could be made from a Science Fair “75 in 1" or “160 in 1" Electronic Project Kit by meticulously tucking colored wires into tiny springs until — voilà!—the crystal radio we’d built began pulling in KDKA-AM, whose hilltop tower was half a mile away from our house.

Long before Apple Store browsing became, heaven help us, a date-night activity, gazing with the earliest pangs of tech lust at the Tandy TRS-80 personal computer and marveling at the sophistication of the 5 1/4-inch floppy disk that so outshone its clunky 8-inch elder brother.

Realistic. Archer. Science Fair. Tandy. Multiple brand names that all pointed back to one magical hardware store cum gadget emporium brimming with items that were surely the many love children of a lunchtime dalliance between the one of Capt. James T. Kirk’s communicators and the Jetsons’ maid, Rosie: Radio Shack.

I THOUGHT OF THAT PERIOD of my life this week when I learned that the final Radio Shack in Maryland was closing, following many hundreds of its brethren around the country since RadioShack Corporation filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy a decade ago. To me, that filing seemed to herald the official close of an era that had, for all practical purposes, ended years earlier — an epoch of wires, springs, switches and molded plastic that, taken together, had quietly trumpeted an Age of Possibility for Americans of a certain generation. If today’s digital age eventually became the main event for our planet, then the era of Radio Shack — or, to be fair, my era of Radio Shack, the mid- to late 1970s — represented the exciting preview of coming attractions.

Radio Shack emerged at a moment when there was barely radio for which to have a shack. It opened its doors as a mail-order outfit in 1921, the year after KDKA became the first commercial radio station to begin broadcasting. As it grew, Radio Shack became a Valhalla for countless tomorrow-minded tinkerers. It stayed that way for a long time, eventually shifting to a business model in which marquee items like “hi-fis” took center stage, buttressed by endless shelves of glorious miscellany, the 1970s electronics world’s equivalent of Phillips screws and Allen keys.

By the 1970s, though, Radio Shack had effectively become a way station between the full-on Jetsonian futurism of the 1960s and the next era that was lurking just around the corner — that of the internet, the smartphone and the cloud.

That’s what made Radio Shack so central to those of us who experienced it in that cultural moment: While it possessed certain elements of the early virtual world, it was unrepentantly, proudly located in the physical one.

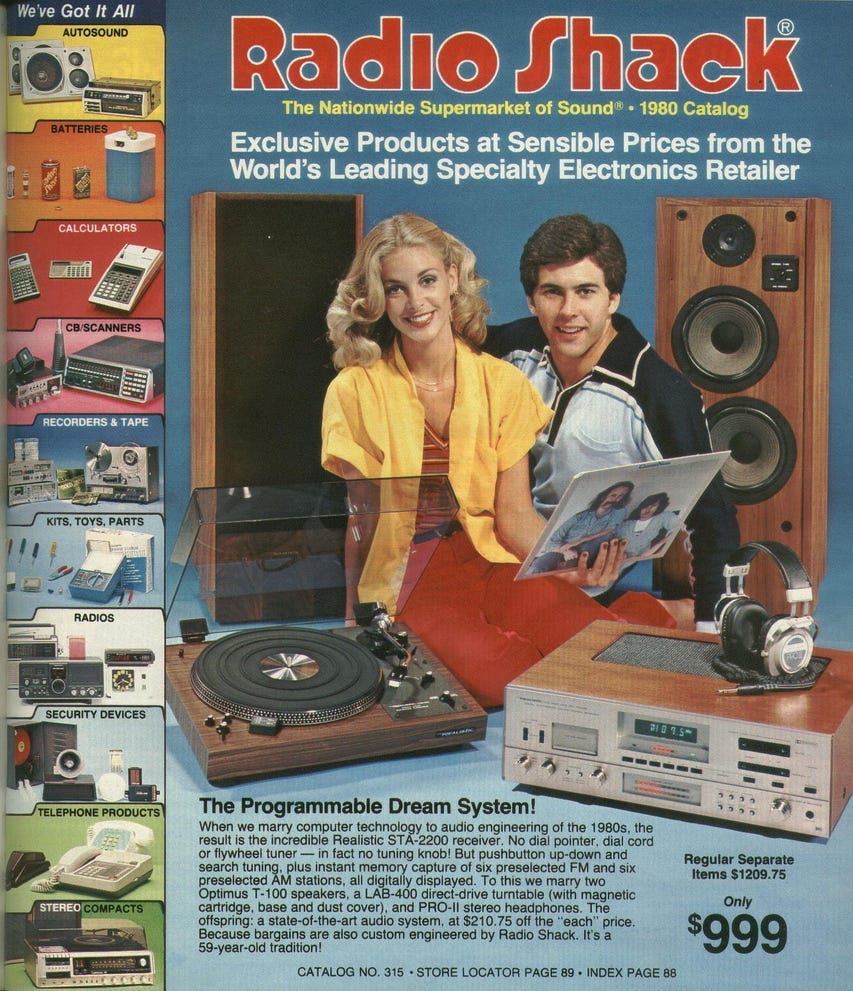

Sure, it had the pre-echoes of cyberspace in its TV games and its early computers, but there was something solid and tangible about what percolated in the pulpy pages of its addictive yearly catalog and beneath the storefront sign with that early digital-age logo. Radio Shacks were always overflowing with walls and shelves of tiny items in those days, nothing like the sparse white landscape of an Apple Store. When you walked in, you’d be confronted with exuberant mashups of metal, plastic and even wood, all packaged under those poetic, even whimsical (“Archer Micro Space Patrol”) house brands.

You were just as likely to stop in for a 1/2" headphone jack, a soldering iron or a pack of Enercell 9-volt batteries as you were for something snazzier, like the memorable “Flavoradio,” the epitome of 1970s sensibility, offered in nearly a dozen fruity hues so you could listen to music while downing your taco-flavored Doritos or popping a Dynamint. At about $6.95, the Flavoradio was wildly popular in my own adolescent circles (we still called it a “transistor radio”), and understandably so: Whether you chose pistachio, plum or blueberry, they represented the ascending coolness of consumer electronics. The Flavoradio and countless other small-canvas pieces of consumer tech formed the bridge from the “Dazed & Confused” sensibility to “Revenge of the Nerds” and, ultimately, to the lines that still form each time a new iteration of the iPhone is released.

At Radio Shack, even the high-end items often were suffused with that combination of shiny chrome and plastic that summoned both the streamlined appliances of the 1950s kitchen and the ray-gun aesthetic of the 1950s drive-in. This was not seamless, SkyMall-style tech. It was equally at home in my father’s basement workshop, brimming with small jars of screws, electrical-tape-spliced extension cords and partially reassembled transistor radios. Sure, the products of Radio Shack could be sleek, but the overall effect of the place was the knobs and clicks and open wires of visceral experience. Like the world at large, it wasn’t yet all about silent touch screens and wifi and “messages from invisible sources — what some people think of as progress,” as a suspicious Al Swearingen put it once in the HBO Old West drama “Deadwood,” speaking derisively of the fast-encroaching telegraph.

MY LAST substantive tryst with Radio Shack (beyond purchasing batteries) was toward the end of the 1980s, as a student journalist. I had attached myself to a talented professional reporter who would file from the scene of news events using a TRS-80 Model 100, the Macbook Air of its day. Watching him on assignment in some small Pennsylvania town, tapping away on thick black keys the words he was about to send to the world, reminded me again, fleetingly, of what made Radio Shack so exciting.

Then the Information Age descended.

Tech sexiness moved on to the next generation of bright young things—items with names like DiscMan, MiniSport, ThinkPad, PalmPilot, Newton. Radio Shack became a victim of what it wrought. In the race to the future, it got lapped — by Circuit City, by Best Buy, by Amazon, and in the end by innovation itself. It struggled to hold on, first by becoming RadioShack (minus the space), then just “The Shack” in an attempt to turn itself into a hip riff. Not much happened. In an era when the once-ubiquitous 9-volt battery now seems restricted largely to smoke alarms, Radio Shack started coming across as Best Buy’s eccentric old uncle or maybe Dr. Brown from “Back to the Future” — the guy who seemed slightly out of sync but, if you got him going after Thanksgiving dinner and a few snorts of whiskey, knew a lot of cool and useful stuff.

The last time I was in a Radio Shack, to buy a hand-cranked Red Cross emergency-band receiver, I felt as if I was walking through an almost aggressively generic electronics store. Familiar brand names abounded, but none of them belonged to Radio Shack. Everything seemed mobile-phone-focused. The heady days of Realistic and Archer and Science Fair and working with your hands felt distant and dusty. One day I looked on the company’s website, and the only RadioShack-branded item visible on the home page was a battery pack to power the very devices and innovations that had rendered it something of a relic. Somehow, it seemed appropriate.

Everything has a lineage, even the things we think of as the most cutting edge. Radio Shack was one patriarch of an extended family of thought and possibility that led us straight to the Walkman/IBM-PC 1980s, the Microsoft Windows 3.1/World Wide Web 1990s and the Macbook Air/iPhone/cloud-computing 21st century. And so I watched my sons grow up, sitting on their own floors with their own devices, doing similar things with music and radio and back-channel communication. They, too, have become tinkerers of their own emerging era. But their tools are microprocessors and multitouch screens and silent fingers instead of wires and springs and transistors and clicks and clacks.

Messages from invisible sources abound. As I write this, Spotify is playing in the background on a computer as different from the earliest TRS-80 as I am from a Pleistocene-era australopithecus. WGN and CKLW broadcasts are at my fingertips, and I no longer have to stay up late to listen. I don’t even need a “transistor radio.”

And yet: There is, in the end, little difference. Humans use tools. Tools evolve, and we leave some behind. And still, somewhere between 8-track and the cloud, between hi-fi and wifi, between bicentennial-era tinkering and contemporary, microprocessor-driven object lust, the possibility of Radio Shack lives on.

Further reading from me:

“Super 8 message: Technology not our friend,” a piece I wrote in 2011.

“Analog’s Twilight,” a piece I wrote in 2008 about the tipping point at which the digital was replacing the tangible.

So many personal touchstones here, including 8-tracks, the Crosby/Nash LP jacket on the '80 catalog cover and the TRS-80 bemoaned ("Trash-80") by Detroit News colleagues who griped about audio couplers incompatible with some pay phones and motel desksets.

We were lucky to be part of that era-straddling transition, with unimagined marvels "lurking just around the corner." Your skilled phrasemaking distills it perfectly as "the bridge from the 'Dazed & Confused' sensibility to 'Revenge of the Nerds.'" Good times.

Phrase-crafting chops shine again in "the pre-echoes of cyberspace." A lesser stylist might've gone with prequels.

And thanks for the time and rabbit hole tumbles that yield the bonus of rewarding links to nostalgic images, memories and the surprise that Sky Mall lives as an online catalog (https://skymall.com/).

You never disappoint, Ted, and this sundae is a sweet treat indeed.

Very good read!