ABOARD THE AMTRAK PENNSYLVANIAN EAST OF PITTSBURGH

THE DAY IS JUST BEGINNING, and on this sunny Sunday morning all is still. Our train slices through the landscape in near silence, its rattling barely perceptible even to the sleepy travelers within its metal confines.

We hurtle east out of Pittsburgh, unnoticed in the mist of dawn — “like an arrow shot from a bow,” as an old American railroad song once put it. Soon, we are cutting through the sedimentary municipal layers of the city’s outskirts: Wilkinsburg. Turtle Creek. Wilmerding. Irwin. Jeannette. Greensburg. And Latrobe, with its views of the houses that one of its favorite sons, Fred Rogers, imported into his television program to create a landscape as familiar to a generation of children as their own neighborhoods.

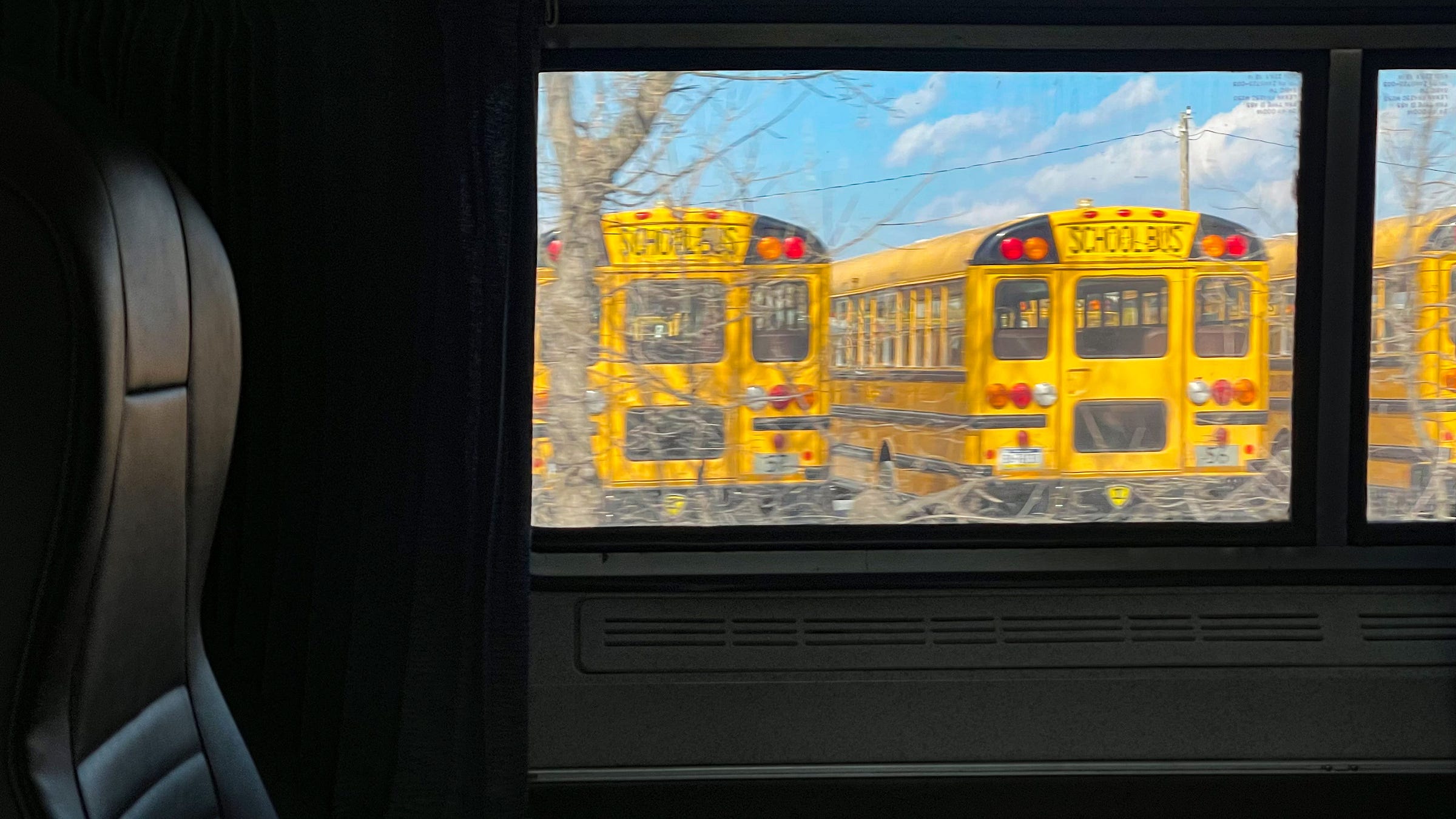

On these types of pocket adventures, it is angle as much as substance that intrigues. The elongated capsule of metal called the Pennsylvanian is, like so many before it across so many diverse landscapes, a subtle interloper into worlds we might never otherwise see.

In an early episode of the radio show “This American Life,” the humorist John Hodgman poses to listeners a choice: Would you rather be able to fly or be invisible? How you answer this question, he posits, opens a window into your personality, or at least into your character. Invisibility is cast as something just a bit untoward, an ability that possesses a whiff of subterfuge and a pinch of impropriety.

On trains, though, we are innocuously invisible — or at least unnoticed. At certain moments, this offers a backstage pass to the mechanics behind the world. Just as important, it reveals them to us from oblique angles that everyday life rarely offers. From trains, you see life from behind, from above, from below, from the sides. You see life unplanned, often unadorned, sometimes not really meant for public view.

Americans have built themselves into a nation of unrepentant forward-facers. In putting ourselves out there, in pushing outward, we tend to define ourselves by the street-facing shop window far more than the storeroom in the back.

Yet sometimes, as the train can remind us, life without the makeup on can be the most interesting life of all.

WE WANT TO SEE each other, to sample each other, to jack into each other’s worlds and see behind all the curtains. Why else would we have so vigorously built such a voyeuristic society? Why else reality TV, Instagram, Twitter, Tik Tok?

This statement is, of course, true only to a point. The same country that adores authenticity also venerates packaging. That means, oxymoronically, that packaged authenticity is often the most popular thing going.

Long-distance train rides, then, offer something quietly transgressive: unpackaged authenticity. To ride the rails — something unusual these days outside of the commuting context — is to see places that people don’t always prepare for public observation. The train window, like so much else nowadays, is yet another screen.

In this shadow (to some of us) world, hoarders and near-hoarders abound. In an era of increasing acquisitions and increasing disposability, the things we no longer desire often end up on back porches, in back yards, cast aside from daily life.

From the well-worn train tracks of the Keystone Corridor, some of that is visible. The first three hours of the Pennsylvanian’s route alone wind through towns and in-betweens that could excite even the jaded likes of Mike Wolfe from “American Pickers.” Old cars abound. Behind factories and warehouses sit pallets surely from as far back as the Nixon administration, their days of holding up fresh incoming goods long gone. Garages and old sheds sit, inviting us to wonder what’s behind their doors.

The chairs you no longer want? The back porch might be the place for those. The house painting that’s long overdue? Maybe save a few bucks by not adding a new coat to the side that only faces the railroad tracks. The car that there’s no extra money to fix one more time? Leave it out back; get to it another day.

But neglect isn’t the only part of this story. “Outside lies magic,” the historian John Stilgoe, an incisive watcher of the vernacular landscape, famously said.

It is true here. From the train I see houses old enough that they were designed to face the passing railroad tracks, holdovers from the Pennsylvania Railroad days when those tracks were as much Main Street as the roads. From raised hills coming into towns like Latrobe, I see oddly diagonal vistas of neighborhoods and roads that no one in a car would have the opportunity to glimpse. From sunken pass-throughs that traverse Wilkinsburg and Wilmerding, I gaze up at bridges and apartment buildings and houses whose grandeur — probably invisible to their occupants on any given day — feels somehow epic.

Later, through the lush late-summer greens of Blair, Huntingdon and Mifflin counties, I see houses, tiny workshops and sometimes entire towns peek through the thick woods around the tracks. In front, they face small roads; in back, they face us, challenging us to make sense of them, to understand the activities and people who might be within.

That they do challenge us in this way, as seen from these vantage points, is a deeply interesting concept. We are challenged by oblique angles and unusual perspectives for the simple reason that they are unusual to us; that is why, whenever you watch an Alfred Hitchcock film, the visuals are so memorable. He makes you see normal, regular things from above, from below, from acute angles, from the shadows on the side — everywhere but where you’re accustomed to seeing them. It is at once unsettling and illuminating. No wonder his work — including “Rear Window,” which addressed a voyeuristic urban version of looking into people’s unvarnished lives — influenced cinematic visuals so deeply.

Migrate this notion to the train ride, and you realize: You can learn a lot from these oblique and unusual perspectives on American familiarity that drift by outside the window.

A train is very different from, say, the interstate highways — walled-off incisions into the landscape designed to help us bypass the communities they traverse. Trains, which came along earlier in American culture, interface with life in a different way. They come right into the middle of towns, interacting with them rather than avoiding them. In many places, the membrane between the track and life alongside it is thin or even nonexistent.

And they carry stories from one community to others. They have long been symbols of going to new places — or of being left behind. “But those people keep a-moving, and that’s what tortures me,” Johnny Cash’s incarcerated protagonist famously sings in “Folsom Prison Blues” about the train going by. (In fairness, he did shoot a man in Reno just to watch him die.)

Usually, though, the perspective focuses upon either the plight of the person watching the train go by or the destination of the person aboard. Rarely do we consider the implied, silent and generally unconsummated relationship that those aboard the train have with those in the landscape outside it. Those two worlds — even in old Hollywood Westerns, where train travel often played a significant role — rarely interact in that way.

That’s part of what intrigues me as I look out upon this deserted Sunday-morning landscape. Because here’s another thing Americans aren’t so good at these days (and arguably any days): making the effort to put ourselves in the other person’s shoes.

To see prosaic things and prosaic landscapes in new ways perhaps ignites dormant synapses, burning neural pathways that have fallen into disuse or have never been used at all. And maybe, just maybe, that kinesis can make us ask the broader questions that are some of American culture’s most pressing at this particular uneasy moment:

Is there a different way to see all this? Are there perspectives that I haven’t considered?

WHERE ARE ALL the people, though?

The first episode of the original “Twilight Zone” series, which aired on Oct. 2, 1959, was called “Where Is Everybody?” Without giving it away (granted, it aired 64 years ago), it depicts someone stranded in a small town that seems to contain no people. He has lost the sense of where he is or even who he is. That liminal state is sometimes how it feels when you’re being carried by the train through the hills and towns and quiet back yards of the mid-Atlantic.

Only occasionally will a live human being make a cameo along the tracks in a place other than a depot. This morning, just past the Tyrone station in Blair County, a man stood by the tracks in the woods with a walking stick and an open shirt. He was about 70. He gazed up at our windows. He had a look in his eyes that was either empty or contemplative. He might have been a hiker. He might have been homeless. I lacked the information to assess which.

In the back yards, as you pass, sometimes you do see people moving about in their personal Pennsylvanian dioramas. Some are working — on their house, on a car, on a garden. Some sit on outdoor chairs, part of the landscape of itemry that dots the unseen parts of their property. Now and then one will wave at the train — though that’s the exception rather than the rule.

Watching their distant faces, I feel a bit of shame. I fear I’m a dilettante, a tourist in other lives I know nothing about. Maybe I’m romanticizing them like I do the structures behind them and the items around them. Maybe I’m looking for an America where they and I both fit in. Maybe that’s an utterly ridiculous notion.

Or maybe not. If you can resist stereotyping people or being dismissive of them, perhaps there is value in observing.

In the insular, Big Sort world of 2023, each of us comes equipped with our own personal moat. They take on various shapes — a fence, a car, an iPhone, an attitude — even as they ensure that fewer and fewer of us encounter fellow Americans who are unlike us. We gaze at others through our biases, look askance at them, make judgments about the entireties of their beings from a single statement or social media post. I sometimes worry that we don’t really want to know more, that the way we’ve been trained for generations to consume American stories through a sometimes simplistic Hollywood lens has discouraged us from developing the tools to go deeper.

So I think the observation of people and places we have nothing to do with, along a long-distance train trip — observation grounded in real life, not mediated by the entertainment industry — is invaluable.

I think of the scene I saw in Latrobe this morning. We pulled into town on the train, passing through back yards and over roads, seeing more of the community in four fleeting minutes than you might notice driving through in a car. I thought about the miniature neighborhood that Mister Rogers, the Latrobe native, had built from wood and paint for his television program — an elaborate model with such clear echoes of the views I saw this morning.

His foundational message was a simple one, distilled to elemental potency for a very young audience: If we learn about each other, if we frame the world as a neighborhood and build our really-seeing-each-other muscles, things might just get a little better for all of us.

With that, I must run. The next train station is just ahead. Time to put my head up and look outward. It’s a window, not a screen. It’s the world.

What a wonderful read, Ted!

One of the best trips of my life was by train Chicago-Seattle then Seattle all the way back to NY. It forever changed my perception of the country and its size and scale and beauty. The variety of travelers was amazing -- military, Amish, you name it. I did it of necessity but am very glad I did; now places like Minot, ND are real memories, not just dots on a map. I also once took the train from NY to Minneapolis to make sure I got there for a paid speaking engagement as planes were likely to be grounded due to bad weather.