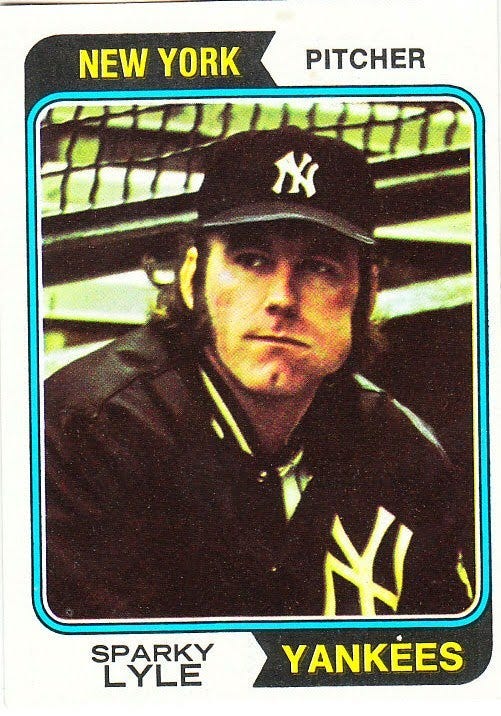

SUMMER 1978. Sparky Lyle of the New York Yankees — a team I have been brought up by my Cleveland-born, Detroit-bred father to despise — is one of the most popular baseball players in America.

Sure, his handlebar mustache and his renowned prankster demeanor make him star material for baseball-obsessed young fans. And of course his pitching — an early closer, or “fireman,” he was the first reliever to win the Cy Young Award, in 1977 — is regularly thrilling.

But I can’t lie — it’s also the chaw of looseleaf chewing tobacco that protrudes ubiquitously from his left cheek.

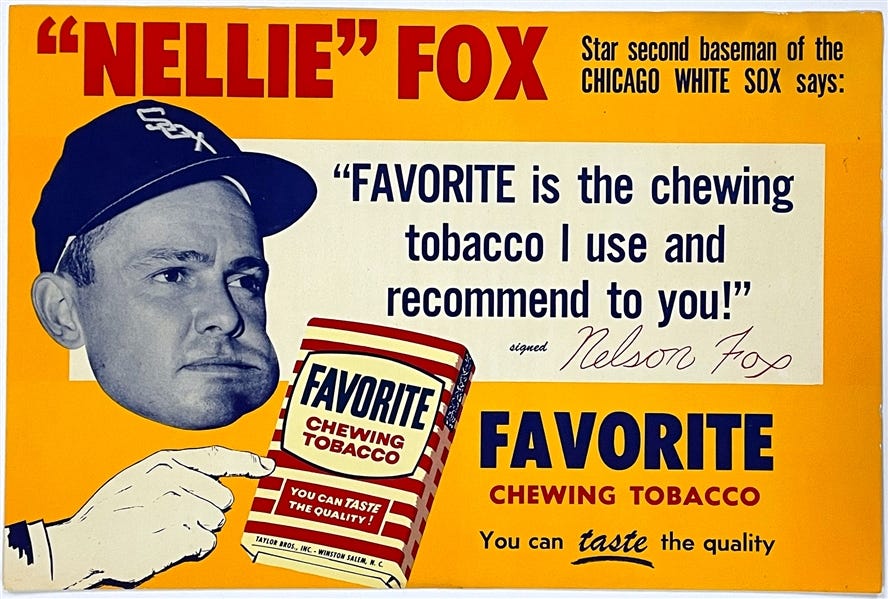

Lyle didn’t just chew tobacco; he reveled in it. Years before baseball decided, quite reasonably, that tobacco chewing wasn’t a good look for a sport that was supposed to provide role models for the youth, many photos of Lyle showed him, like a squirrel with an acorn tucked away, masticating a chaw and poised to spit.

This was, of course, a grittier era of baseball; the first batch of Big League Chew bubble gum (co-created by Jim Bouton of “Ball Four” fame) was still nearly a year away. What 10-year-old didn’t want to emulate his favorite ballplayers, in activities both wholesome and edgy?

I go to my father. Dad, I say. I want to try chewing tobacco.

My mother is sitting beside him. They are drinking bottles of Stroh’s after dinner. She raises an eyebrow and gives my father what, 30 years hence, would become widely known as side-eye.

“Sure,” my father says, studiously avoiding my mother’s look.

The next day we go out to DeBaldo’s, the local gardening supply place-slash-general store. I cannot believe this is happening. Straight-faced, he asks for a packet of Levi Garrett, for which Lyle does commercials (yes, children, gather round and hear a tale of the days when chewing tobacco was advertised on television). They don’t have it, so we settle for Mail Pouch, whose logo is painted on the sides of barns across the republic.

I am chatting excitedly about Sparky Lyle as we depart DeBaldo’s. My father’s only comment: “This does not mean I support the Yankees in any way, shape or form.”

WE PROCEED HOME. We walk past my mother, whose side-eye has ceased. Does she know something I don’t? Have they talked?

It’s probably nothing, I conclude. After all, these are the peak Gen-X years, when children were feral little goblins and parents were … less supervisory.

Nevertheless, I still don’t quite get it. Both of my parents smoked for 25 years (Chesterfield and Viceroy, if you’re curious) and quit when I was born. This doesn’t track. Something feels amiss. But reading the room is still many years away for me. Some would argue it remains so.

We head out the side door to a small wooden porch with a set of steps that lead down to the woods north of our house.

“Here you go,” my father says, handing me the sleeve of Mail Pouch. “Knock yourself out.”

I remind you: I am 10.

Feeling subversive, I tear open the pouch. I grab a chaw. I put it in my mouth and begin to gnaw at it, making sure I was stuffing it into my left cheek just like the players I’ve seen on the cards. The tobacco flavor begins to flood my mouth.

It is … not pleasant. It is rich and earthy and bitter. It stings. I gulp. I look up at my father. Then I make my mistake.

I swallow my spit. No one told me not to. Sure, I’ve seen players spit tobacco, but I didn’t know you HAD to.

Then, in quick succession: My eyes bulge. My bile rises. My father looks on, arms crossed. If I didn’t know better, I’d swear a smile was about to break out across his bearded face.

I lean over the porch and throw up prodigiously onto the yard below.

I don’t remember much after that. But one thing is clear: That day was 47 years ago. I have not tasted chewing tobacco since.

EXACTLY TWENTY SUMMERS LATER, my father and I are on a trip to visit the Field of Dreams in Dyersville, Iowa. In the car, since we are discussing baseball matters and father-son matters, I ask him: Why did you let me do that? I was 10. What the hell were you thinking?

He responds, enunciating each word: “And when, pray tell, was the next time you chewed tobacco after that?”

He knows the answer, of course. “I rest my case,” he says.

And that smile that started to peek out on our porch two decades earlier? He’d been saving it. And in a 1990 blue Nissan Sentra along Interstate 80 that is hurtling west and contains two adults who happen to be father and son, that decades-delayed smile of my dad’s finally blooms.

IF YOU’VE ACTUALLY READ THIS FAR:

I wrote this piece four years ago after an unfortunate spate of deaths of 1970s ballplayers.

More on that Field of Dreams trip I took him on in 1998.

And in case you’re curious about my father beyond his relationship with chewing tobacco, here’s the eulogy I delivered at his memorial service in 2015.

Wonderful piece, Ted! You are blessed by these memories

Wonderful story! And the supporting images are all top-notch - that page of "chaw cheek" baseball cards is simply magnificent.