Close, But No Cigar Band

The curious, tobacco-inflected correspondence between my adolescent grandfather and Mark Twain.

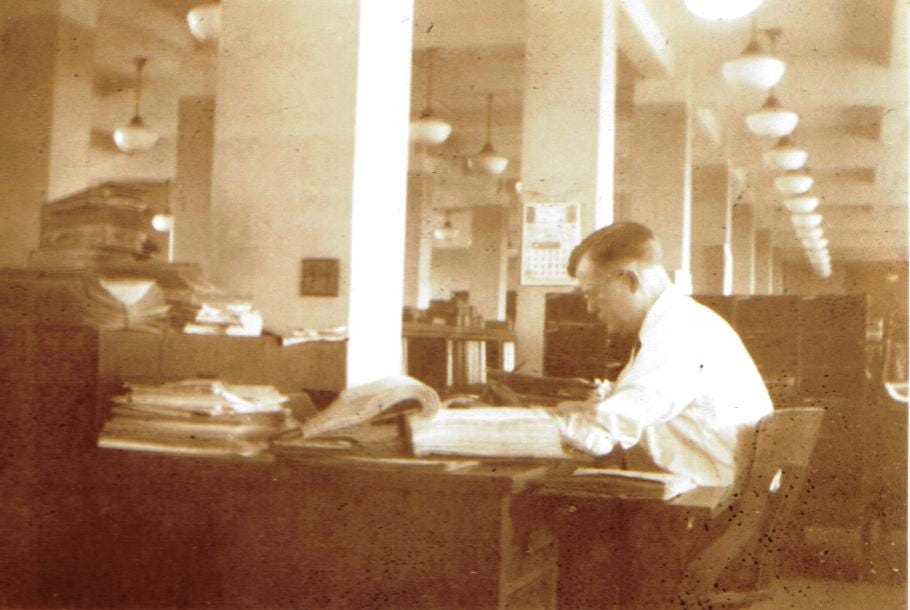

I NEVER KNEW my paternal grandfather and namesake, Edward Mason Anthony Sr., who died a decade and a half before I was born. I can’t remember my grandmother ever speaking of him. What little I know of him came from my father, who told me he’d been a clerk for the New York Central Railroad — a quiet, reserved man who’d had polio as a teenager and walked with a limp, who was dedicated to tracing his family history, who occasionally beheaded chickens and whose final words, while expiring of a heart attack one December morning in 1954, were, simply, “I’m sorry.”

I know a bit about his ardor for my grandmother from a single penciled love letter that outlived both of them. I know that he loved baseball and had two tickets to the fourth game of the 1920 World Series, in which his hometown Cleveland Indians defeated the Brooklyn Robins (League Park, section 15, row R) — but that he never used them. I know that because today, a century later, I have the tickets. They are untorn and intact.

Impressions. Slivers of a life. Scaffolding without a lot of detail. I always wished I knew more.

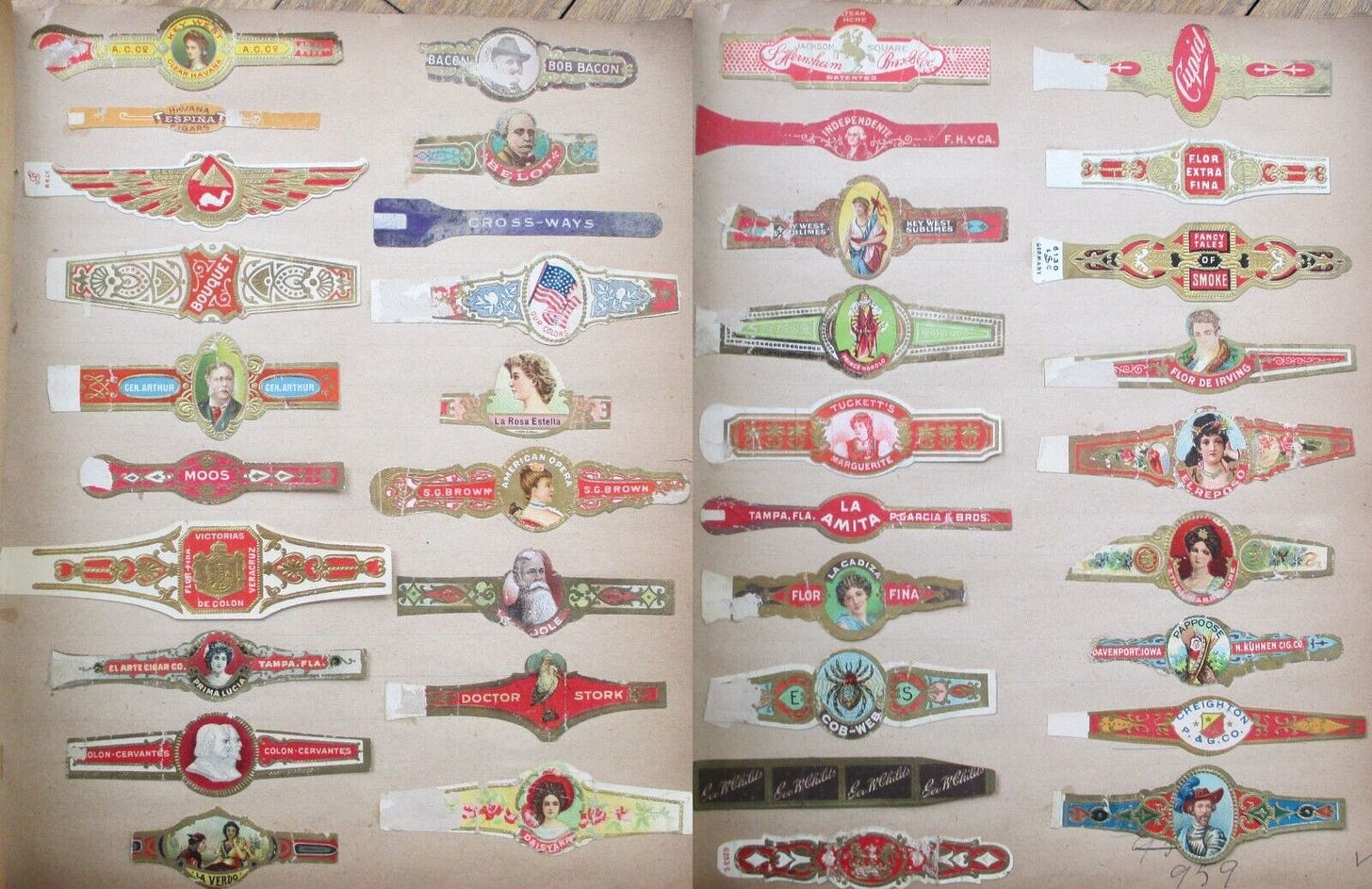

I did know, though, that he had faithfully collected cigar bands. How? Because in the closet of my father’s study when I was little — the study where I write this tonight, decades later — sat three thick, brown-covered pocket notebooks bursting at the seams with the early 20th-century cigar labels that my grandfather had pasted in over the years.

He never smoked cigars, only cigarettes, and my father always seemed bemused at the fact that he had become the inadvertent heir to this collection of beautiful pieces of commercial art in miniature. In one of my father’s rare nods to practicality over history, when I was about 9 he sold the entire collection to a history-minded acquaintance who ran the local Ford dealership.

Aside from the occasional fleeting memory, I never thought much about the cigar bands again other than to wish in passing here and there that my father hadn’t gotten rid of them.

That is, until the day in 2012 when I got an email from one of the world’s most prolific writers on Mark Twain.

SAMUEL LANGHORNE CLEMENS, aka Mark Twain (1835-1910), was renowned for his affinity to cigars. Many of the quintessential images of him show him wearing his trademark white suit and holding or puffing on a stogie. Among the countless quotes attributed to him (you have to be careful quoting someone like Mark Twain, because legend hangs heavy): “If smoking cigars is not permitted in heaven, I won’t go.” And “More than one cigar at a time is excessive smoking.”

Suffice it to say that the man liked cigars, liked to talk about cigars, liked to be seen with cigars and wreathed in cigar smoke.

In 2012, R. Kent Rasmussen, who has written multiple books about Twain, turned his attention to the man of letters’ letters. In Dear Mark Twain: Letters from His Readers, he took advantage of Clemens’ propensity to hold onto the mail sent to him between 1863 and his death in 1910, and pulled together something fascinating: an annotated, contextualized look at some of the missives mailed to the author, and the people who sent them.

I find this enthralling. The notion of history through the people who write to someone is an unusual lens through which to look at the past, and it reveals everyday lives — a cross-section of them, at least — in interesting configurations that we might not see otherwise, particularly that far back in the American past. As Clemens put it in one story, quoted by Rasmussen: “A man’s experiences of life are a book, and there was never yet an uninteresting life. Such a thing is an impossibility. Inside of the dullest exterior there is a drama, a comedy and a tragedy.”

Most people in the book who wrote to Clemens had nothing directly to do with the man himself; they simply were drawn to his fame and talent and wanted to connect, just as Twitter and Instagram users can connect with — and sometimes interact with — celebrities today. Some wanted money. Some wanted to criticize his work or lay into him. Some wanted to out-Twain him with their own clever words. Some sought writing help. Some just hoped for a reply in his handwriting — a bespoke autograph through the mails. One asked him to name his favorite flower.

Then there was my grandfather. He wanted some cigar bands.

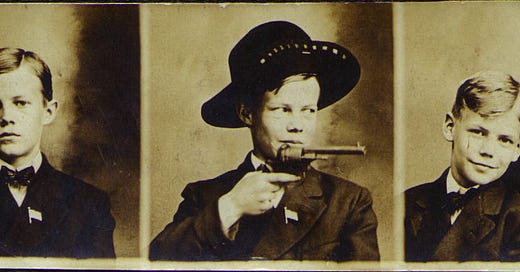

Edward Mason Anthony was 13, living in Cleveland and — I was about to learn — a budding and already published young writer. One day in September 1907, this boy, who would posthumously become my grandfather six decades later, risked a missive to this legendary writer.

3723 W. 41st St.,

Cleveland, O.,

Sept. 29, 1907

Dear Sir,I am a boy who is collecting cigar bands. I have six-hundred different including one hundred-and-fifty different ones with faces on them. In the Chicago Sunday Tribune today, I saw that you smoked a great many cigars “without life belts around them,” but I also saw that you had many boxes of imported cigars around the house. Imported cigars usually have bands around them. Could you send me some of the bands? I do not mind if they are alike as I think bands from New York would be rare and easy to trade with the other collectors around here.

Yours expectantly,

Edward Anthony.

I had no idea about any of this until out of the blue, in August 2012, Rasmussen reached out to me via email and sent me a scan of the letter above. He’d first tried my 90-year-old father, the other Edward Mason Anthony living at the time, but my dad was in the throes of Alzheimer’s and had stopped answering his emails after a disastrous fall several months earlier.

Beyond the Cleveland return address of the old letter, which my father remembered well despite the dementia, I knew immediately that this was my grandfather’s handwriting. I have a sheet of paper from many years later in which, in his looping and slightly slanted cursive, he wrote down all the names of Pullman Sleepers, the elegant railroad cars that traversed America’s tracks. And though this letter to Clemens was written a few months after my grandfather turned 13, his distinctively buttoned-up script was already recognizable.

What I didn’t realize was that my grandfather had been such a precocious writer. I can picture him with fountain pen in hand, earnestly composing that letter, making sure he sounded appropriately — what? — grown up to get the aging and voluble author’s attention. (Rereading it today, I think my favorite thing is the “Yours expectantly.” From a 13-year-old.)

Through my father, I knew that my grandfather had valued writing, though surviving examples had been scarce beyond the love letter and a smattering of other papers. We’ve had writers in the family for generations. My great-great-great grandfather, James Shearman Anthony (1794-1845), was known as “The Rockport Bard” in the township outside Cleveland where he lived.

Rasmussen had more revelations for me in this respect. When I responded, he sent along copies of two pages from a long-gone newspaper called The Cleveland Leader, which I somehow had never come across in my years of researching Anthony family history in the area. He’d found them during his efforts to track down my grandfather’s background. They were from March and November 1904, when my grandfather was 9 and 10 years old respectively. Each was a kids’ page called “For Children,” and each had a contribution from my grandfather.

The earlier page had two cute if unmemorable pieces of verse — though impressive for a 9-year-old. But the later one, a short story about an acorn that grew into an oak tree and went places and became new things, has stuck in my mind for the past decade. Somehow, it connected me with my never-known namesake and showed me that the “quiet, reserved man” my father described — the one who lived through teenage polio and, according to my father, was never quite the same — once dreamed really big.

How do we connect with those who are gone, or with those we never even knew? In the end, we don’t really need séances or dreams. We don’t even need religious faith. Sometimes we can have our conversations with the dead right here on Earth, with nothing supernatural involved. Sometimes all it takes is an unexpected connection.

SO DID MR. CLEMENS end up sending my grandfather some cigar bands? Were the “life belts” of some of Mark Twain’s stogies contained in the notebooks that my father sold to the Ford dealer almost exactly 70 years later? How could we ever know?

Thanks to Kent Rasmussen, we do. And the answer is no.

We know this because a response was given. Mark Twain did not ignore the young Edward Mason Anthony. According to the shorthand on the back of the letter, Clemens dictated this response to his personal secretary that was sent on Oct. 2, 1907:

Mr. C asks me to write for him and say that he has given all the cigar bands from his imported cigars to a little friend who asked for them; and he regrets that he has none.

(Rasmussen notes that Clemens preferred domestic tobacco, and in fact once refused a gift of expensive imported cigars, so the response may not have been a blow-off.)

My father never mentioned a letter from Mark Twain, nor did it turn up in his papers. I wonder if, somewhere in this house, in a box I haven’t been through yet, sits a letter from the author of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. But I can’t imagine it. That’s the kind of thing my father, an elegant writer and man of letters himself, would have been deeply proud of and talked about for years.

Today, on eBay, an assortment of early 20th-century cigar-band collections are available for bidding and buying. I look at the lots advertised and think about the care that went into each one by, in many cases, someone long gone and perhaps forgotten. Each collection is arranged just so, like rare stamps or coins or baseball cards. Everyday curation, just like in the scrapbooks that Twain so famously sold. From the few times my father showed it to me, this is how I remember my grandfather’s collection looking. The commercial culture of the 20th century was emerging and in its first years, and my young grandfather, in Cleveland, was riding one of its first waves.

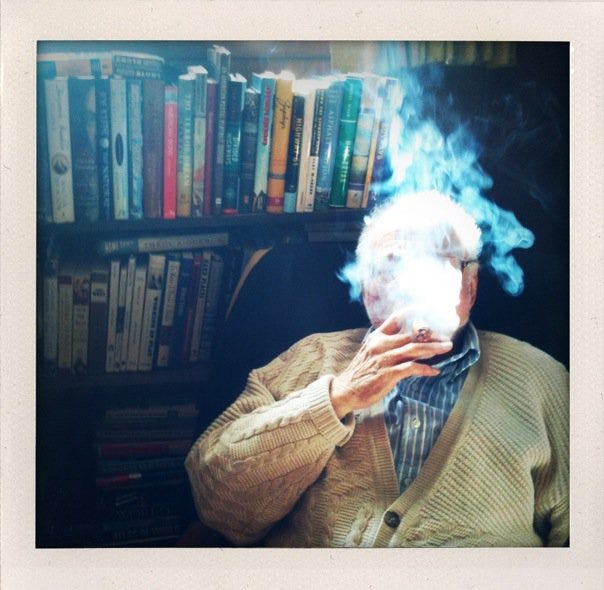

IN HIS LATER YEARS, long after I became an adult, my father and I started the ritual of having an occasional cigar together. Sometimes, in the 1990s, it would be at a nearby lounge called “Uncle Mike’s Cigar Haven.” But more frequently, it would be my excuse to get him walking. Any detriment caused by the cigar, I rationalized, would be offset by the needed exercise that he’d be getting. And so, for 15 years at the back end of his life, whenever I was visiting that’s what we would do.

The last few times before he became too infirm to come over, we’d sit in this room that was once his study and is now mine, and we’d do a transgressively unthinkable thing that, in Samuel Clemens’ era, was commonplace — sit and actually have cigars inside the house.

Sometimes, on contemplative occasions, I’ll have a cigar alone in this magical room and think about those who are gone — my mother, my father, friends who died too soon. Occasionally I’ll think of my grandfather, this newly minted teenager in a house in Cleveland somewhere in far-off 1907, meticulously writing to a literary legend to request some shiny labels that, for some reason, felt important.

And as I write this, I realize: For more than a year, to equip myself for those contemplative occasions, I’ve had an unopened box of cigars sitting behind me on a shelf in the very closet where my father, Edward Mason Anthony Jr., stored the cigar band collection of my grandfather, Edward Mason Anthony Sr., nearly 50 years ago.

The brand of those cigars? Mark Twain, naturally. It says so on the band.

So lovely, all the links threading back in and over time. A recent young student of mine is a relative of Clemens… so this had another twist for me.

I wish your grandfather could have known you. It sounds like you would have had so much to talk about.